Magic, as an art form, has captivated audiences for centuries with its blend of mystique, storyline, and spectacle. It is an ever-evolving narrative, crafted by the hands of its practitioners who, with each shuffle of the cards or ingenious illusion, write a new chapter in its rich history. It is a history that began long before the gasp-inducing performances of Houdini, reaching back to ancient conjurers, but for the sake of our story, let us begin in the era of modern magic with the father of conjuring, Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin.

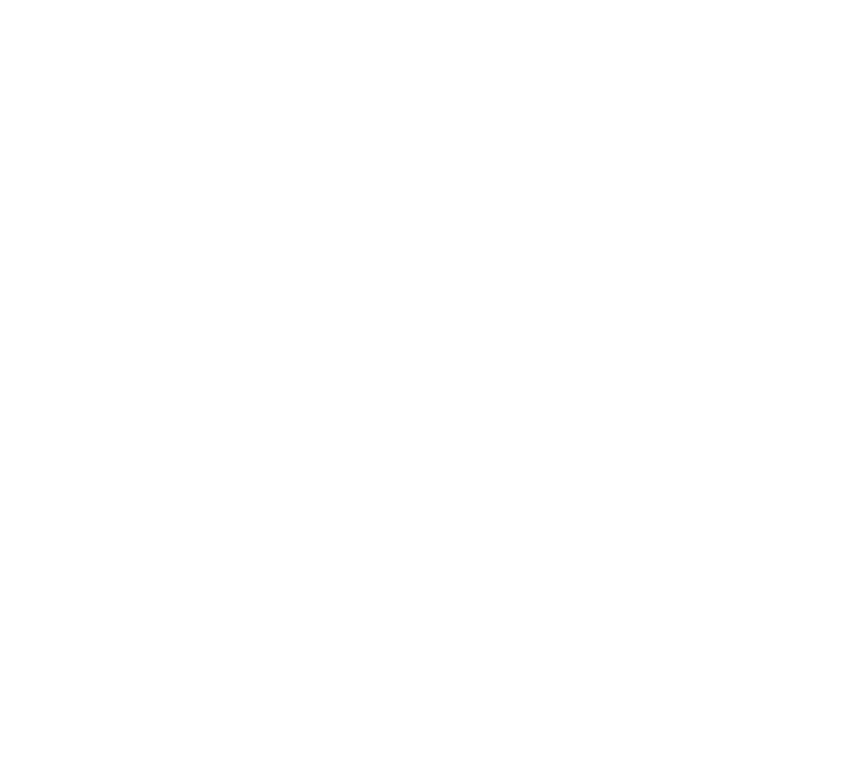

The Birth of Modern Conjuring: Robert-Houdin (1805-1871)

Our story begins in the heart of the 19th century, within the bustling streets of Paris, with a man named Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin.

Long before Robert-Houdin, magic was the province of charlatans and “warlocks” and spiritualists. Entertainers would be cloaked in Orientalist garb, their acts smacking of the carnival rather than the concert hall. Robert-Houdin is famous for stripping away the outlandish costumes and supernatural claims and presenting himself as a gentleman who would perform magic, instead of a mystic or a vagabond. He wore evening attire: coat tails and a top hat (an outfit whose image remains to this day), and he would perform feats that, while spectacular, were rooted in the possible.

Such a metamorphosis, from mystical warlock to polished, formal entertainment did not occur overnight. Born in Blois, France, Robert-Houdin was the son of a watchmaker, and originally pursued watchmaking himself — a vocation that endowed him with the precision and mechanical insight that would prove essential for his later inventions. His turn to magic came about when he received a two-volume set of books on conjuring on accident, intended for a locksmith. The misdelivery was serendipitous and would change the course of magic at large, as the tomes ignited in him a passion for sleight of hand and the science of illusions.

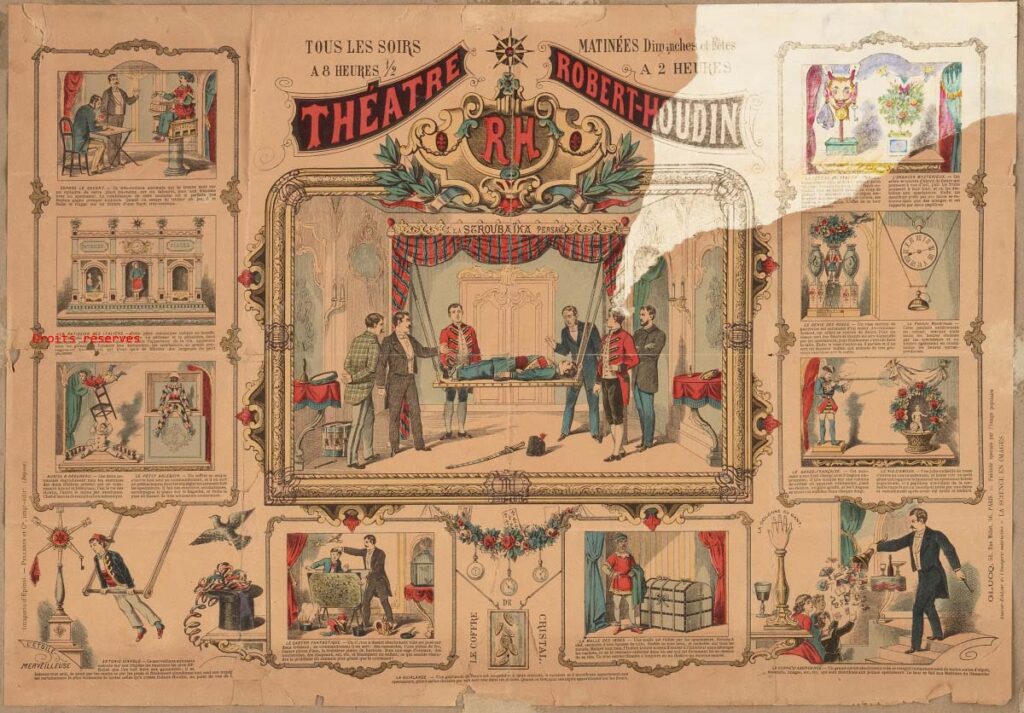

Eschewing the traditional venues of fairs and public squares, Robert-Houdin constructed his own theater in 1845, the Palais Royal, where he staged his Soirées Fantastiques, enchanting Parisian society with an elegance of performance and technical innovation never before seen. One must imagine the Palais Royal as a wonderful crucible of enchantment, where gas lighting, smoke, and mirros combined to create a sense of intimacy and mystery.

One of the main reasons Robert-Houdin is considered the Father of Modern Conjuring is that he was a master of several domains. He was a magician, yes, but also an inventor and showman. His Marvelous Orange Tree Illusion was a marvel of its age, and continues to inspire today. It was a miracle of life: small buds would appear on the barren branches of a tree, blossoming into oranges, which he would then pluck and distribute to the audience. The grand finale had two butterflies appearing, fluttering upward to reveal a handkerchief signed by an audience member, previously vanished. It was this synthesis of mechanical contraption and magical narrative that captivated the public and elevated the art. Today, perhaps, audiences would scream ‘robotics’ and be less impressed. In the 1800s, audiences weren’t so skeptical. His career defines a now-common truth in the world of magic: magicians often stand at the forefront of technology in order to entertain their audiences.

But his influence was not limited to performance. His writings, particularly the 1868 treatise “The Secrets of Conjuring and Magic,” laid bare the magician’s code, revealing how mechanical ingenuity, physical dexterity, and psychological manipulation could achieve the miraculous. Here was one of the first systematic examinations of magical technique, penned by a master practitioner, serving as a lodestar for generations. It’s a book I have in my library; I found a second edition in a used bookstore in college, and couldn’t believe my luck.

Robert-Houdin’s legacy was profound. Not only did he influence the performance style of magicians, but legend has it he was also called upon for diplomatic service. In 1856, he was tasked by Emperor Napoleon III to help quell the unrest in French Algeria by outperforming local marabouts, who were using “magic” to incite rebellion. Robert-Houdin’s spectacular shows, which included an “ethereal suspension” and an “arm that cannot be lifted” illusion, “proved” to the local population that French magic was superior, thus subtly undermining the influence of the religious leaders. This story, where magic conquers all, runs deep in the lore of conjuring history, but who knows what really happened.

It was this ability to reconcile the roles of entertainer, innovator, and even statesman that cements Robert-Houdin’s place at the foundation of modern magic. His insistence on elegance, his embracement of novel technologies (such as the then-revolutionary use of electricity and his automaton-marvels), and his recognition of the importance of narrative and character in performance transformed what was once a craft of deception and cheating into an art form. His shadow reaches far, laying the groundwork not only for the great magicians who followed him but also for the very culture of magic, which began from him to burgeon into a sophisticated, intellectual pursuit. Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin’s footsteps are ones whose echoes are felt in the quiet gasp of every audience that witnesses the impossible made possible.

Harry Houdini (1874-1926)

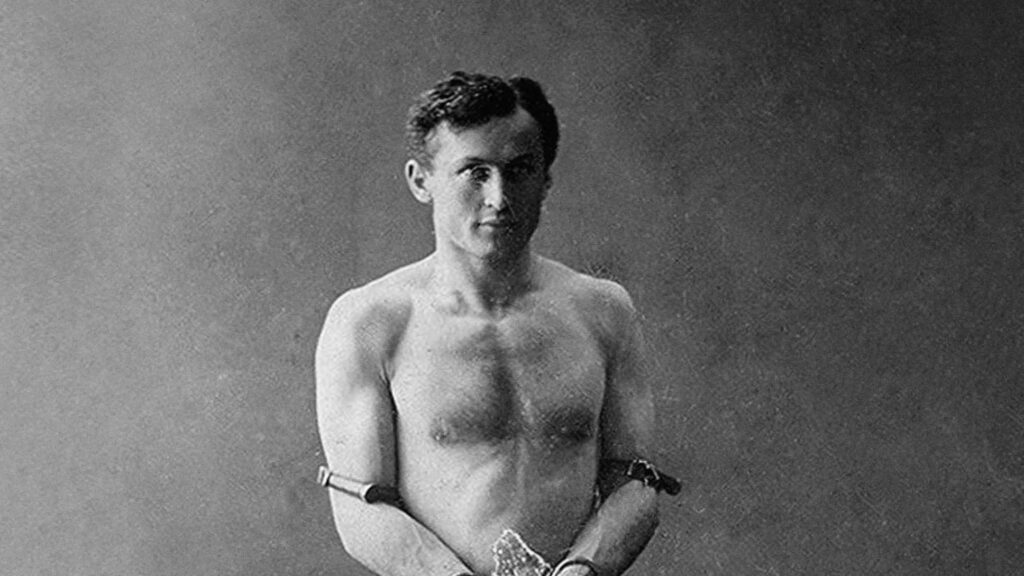

Each new era is a reaction and often a push away from the former. Houdini is no exception. We turn the page from the elegance of salons to the shackled, water-filled confines of escape artistry, where Harry Houdini, born Erich Weisz, would emerge as the archetype of the daredevil performer and the quintessence of the American Dream. Houdini’s story is not simply one of entertainment but a narrative soaked in the essence of transformation and liberation, both literal and metaphorical, at a time where America was a place of dreams and possibilities, and the world order was being shaken to its core.

Born in Hungary, Houdini arrived in America as part of a wave of immigrants chasing opportunity. Early in his career, Houdini struggled in dime museums and sideshows. It wasn’t until he focused on the art of escape that he got his big break. He took his stage name in homage to Robert-Houdin, appending an ‘i’ to signify “like Houdin,” aspiring to parallel the legacy of his hero, and not realizing that adding an ‘i’ to Houdin didn’t mean ‘like Houdini’. Houdini would go on to eclipse Robert-Houdin in fame, becoming the most famous man on earth during his lifetime, and go on to become a name synonymous with magic itself.

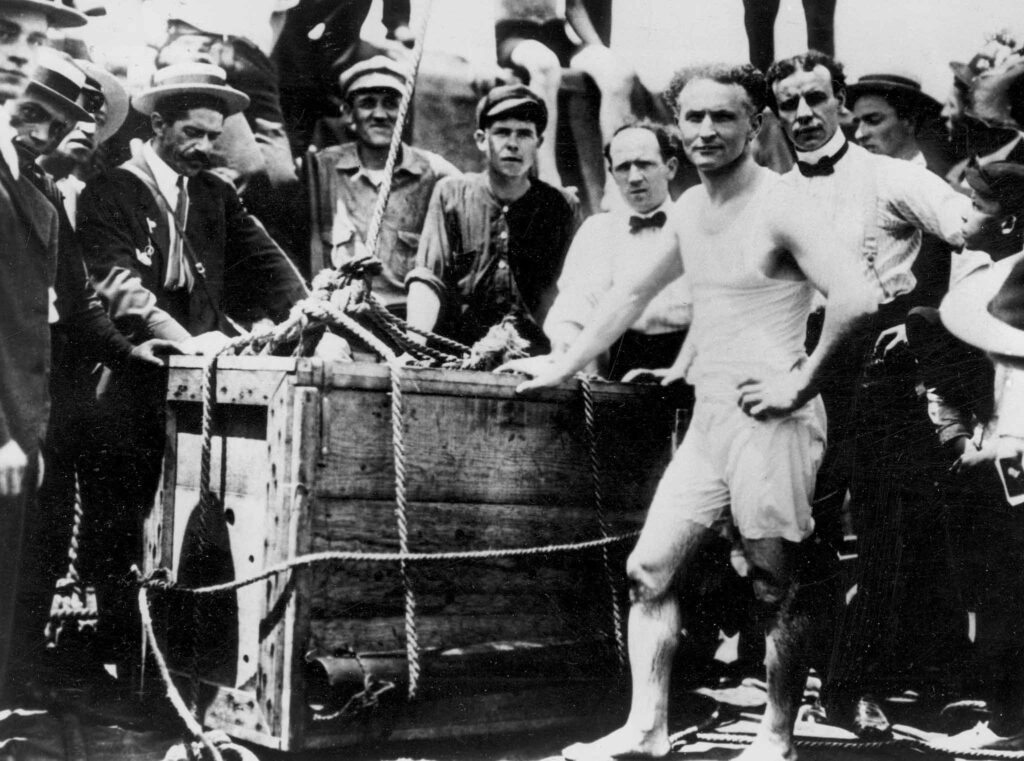

Houdini’s escapes were theatrical masterpieces: from handcuffs, straitjackets, jail cells, and most famously, the Chinese Water Torture Cell, where he was suspended upside-down, in a locked glass cabinet filled with water. Each performance was not merely a stunt but a carefully crafted drama, building suspense to almost unbearable levels before the triumphant escape.

But where did Houdini’s true genius lie? It was not in his sleight of hand or skills of escape, but in his uncanny understanding of publicity and his ability to marry his escapes with the zeitgeist of his time. In an age when the world was rapidly changing, with the Industrial Revolution giving way to the Machine Age, Houdini seemed to symbolically resist the inexorable constraints of technology and society, and demonstrate to the fear-stricken world that humanity itself could not be shackled or contained. He represented the strength of the individual man over the machine, a story that resonates to this day.

Houdini also exhibited a remarkable savvy for self-promotion, leveraging every escape as a media event. He would challenge local police to shackle him with their best cuffs, escape from prisons, and perform death-defying feats in full view of the public, generating headlines and a following that turned his name into a byword for the impossible.

Like Robert-Houdin, Houdini’s impact transcended his performances. Deeply invested in the integrity of his craft, he also spent a significant part of his career debunking spiritualists and fraudulent mediums, which endeared him to the rationalist movements of the time, the big names of science and technology, and asserted magic as an honorable art; one of deception, yes, but honorable deception. His crusade was not just against charlatans but against superstition itself, positioning magic as a celebration of human ingenuity rather than supernatural power.

Publications such as “The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin” (1908) and “Handcuff Secrets” (1909) reveal a complex relationship with his predecessor. While he originally idolized Robert-Houdin, Houdini would later criticize him, alleging exaggerations and fabrications in Robert-Houdin’s own autobiography. This conflict, however, is indicative of a broader narrative in magic, where each generation grapples with the legacies of its forebears, dissecting and reinterpreting the past to forge its identity, while also engaging in the same sins.

Houdini’s death on Halloween of 1926 would itself become legend, fueling a mythos that would inspire countless magicians. His daring and showmanship, his relentless pursuit of wonder against all odds, would set the bar extremely high. Harry Houdini’s escape acts were emblematic of the human spirit’s eternal struggle for freedom—freedom from the physical chains of his tanks and locks, but more profoundly, from the metaphorical chains of limitation and mortality.

In the shadow of Houdini’s grand escapades, magic would inch closer to the mainstream of popular culture, becoming an indelible part of America’s entertainment history. He had not only expanded the audience for magic but had transformed the very nature of spectacle itself, infusing it with a narrative of perseverance and triumph that continues to captivate us to this day.

The Golden Age of Magic

As the curtains fell on Houdini’s illustrious life, the world of magic did not dim. Instead, it sparkled with greater brilliance as it entered what many enthusiasts refer to as the Golden Age of Magic, an era that spanned from the late 1800s into the early 20th century. This was an epoch that saw the flourishing of grand theaters and the ascent of magicians as marquee performers. They were idolized much like movie stars, commanding lavish stages with illusions grander and more fantastical than ever before.

During the Golden Age, magicians such as Howard Thurston, Charles Carter, and Harry Blackstone, Sr. filled theaters with awe-inspiring spectacles and illusions on a scale that dwarfed the intimate parlor tricks of past generations. Howard Thurston, known as “The King of Cards,” took the baton from Houdini in the realm of fame. He showcased a gentle manner and a flair for the dramatic, with illusions such as the famous “Levitating Princess” that left audiences simultaneously mystified and charmed.

Thurston’s rise to prominence was not simply a testament to his skill but also to his showmanship. His touring show “Thurston’s Wonder Show of the Universe” was a colossal production involving eight train cars of equipment and personnel, a testament to the booming popularity and commercial success of magic. Audiences were treated to a plethora of illusions that included vanishing horses, floating ladies, and even illusions that nodded to the technological marvels of the age.

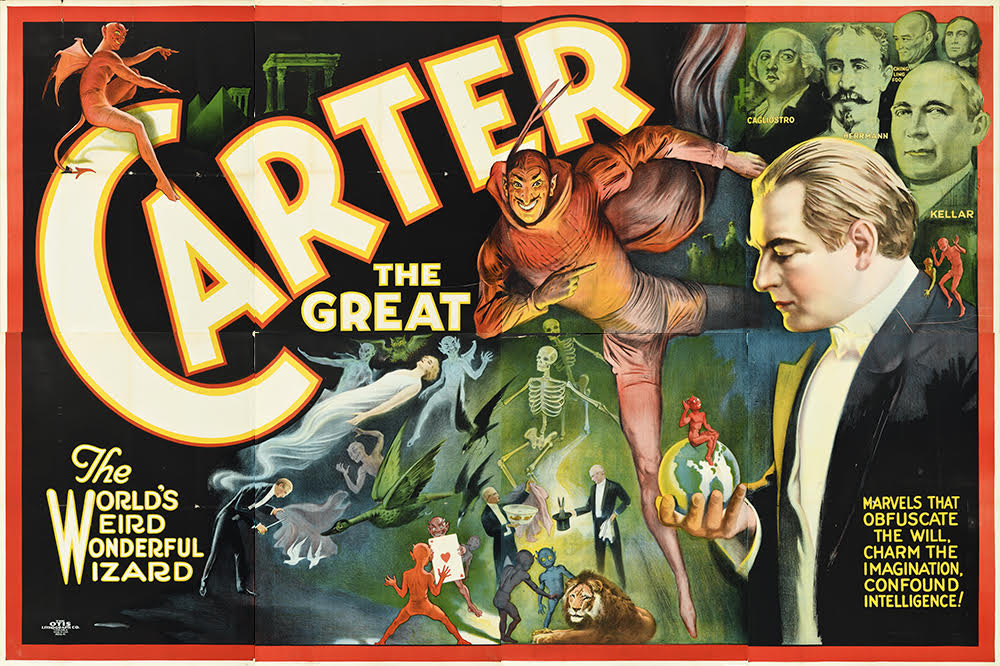

Simultaneously, magicians like Charles Carter, known as Carter the Great, branded his shows with a tantalizing mix of exoticism and adventure. He advertised himself with lavishly illustrated posters that evoked the thrills of pulp novels. His theatrics and branding were critical to his allure, painting him not just as a performer but as an adventurer in the wild, untamed world of magic.

While these magicians captivated audiences with their grand illusions, a parallel trend of close-up magic began to garner its own dedicated following. The names of Dai Vernon, known as “The Professor,” and Max Malini, emerge as the leading figures in this intimate domain. Vernon, in particular, elevated close-up magic to an art form, spending his life perfecting sleight of hand and advocating for naturalness in the execution of magic. It was this devotion to craft that endeared him to fellow magicians and audiences, earning him the reverence of his peers.

But the Golden Age was more than a showcase for technical prowess; it was an embodiment of the era’s spirit. Magic mirrored the extravagance of the roaring twenties and the collective suspension of disbelief. It was as much an escape from the brute realities of the First World War and the Great Depression as it was a celebration of human imagination. The flamboyant illusionists of the time provided a space for society to revel in the impossible, even if just for a moment.

Yet the impact of the Golden Age of Magic extended beyond these temporal escapes. It reinforced the magician’s role in society as a purveyor of wonder and a challenger of perceived realities. Magicians became cultural icons, their names etched into the psyche of a world yearning for a glimpse into the extraordinary.

The narratives of the Golden Age also laid the groundwork for modern performance magic. The scale and grandiosity of the illusions developed during this time would become benchmarks for future performers, their legacy seen in the elaborate Las Vegas shows and television specials that are still popular today. It was a time when magic’s flame burned most brightly, casting its light into the future, illuminating the path for all those who dare to follow in the footsteps of the great conjurers of yesteryear.

The Modern Marvels: Reinventing Magic for a New Age

As the 20th century unfolded, magic found new vessels of expression, chiefly through the wonders of television and a new generation of performers who brilliantly married tradition with contemporary culture. These Modern Marvels have redefined what it means to be a magician, bringing a fusion of narrative, technology, and personality that continues to enchant audiences the world over.

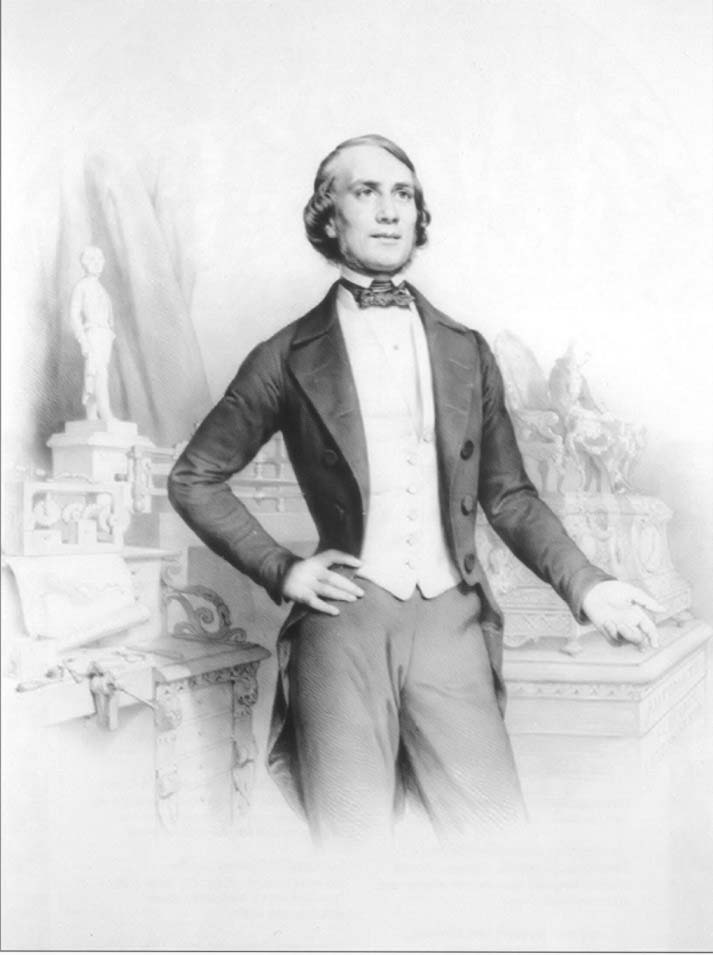

Doug Henning (1947–2000)

In a shift away from the stoic and mysterious, Doug Henning burst onto the scene with a whimsical flair that echoed the psychedelic soul of the 1970s. With his natural charisma and a wardrobe that could only be described as ‘colorfully eclectic,’ he became an emblem of magic’s renaissance. His Broadway spectacle “The Magic Show,” which debuted in 1974, ran for four and a half years, intertwining magic with musical theater in an unprecedented marriage of genres.

His televised annual magic specials introduced a new tradition, one where families could gather and bear witness to feats of wonder from the comfort of their homes. Henning had a particular talent for reviving classic illusions, like “Metamorphosis” and “The Water Torture Cell,” paying homage to Houdini while injecting his distinct brand of joyous energy. It was Henning who made magic cool again, broadening its appeal to a new generation and laying the groundwork for magic’s flourishing popularity on television.

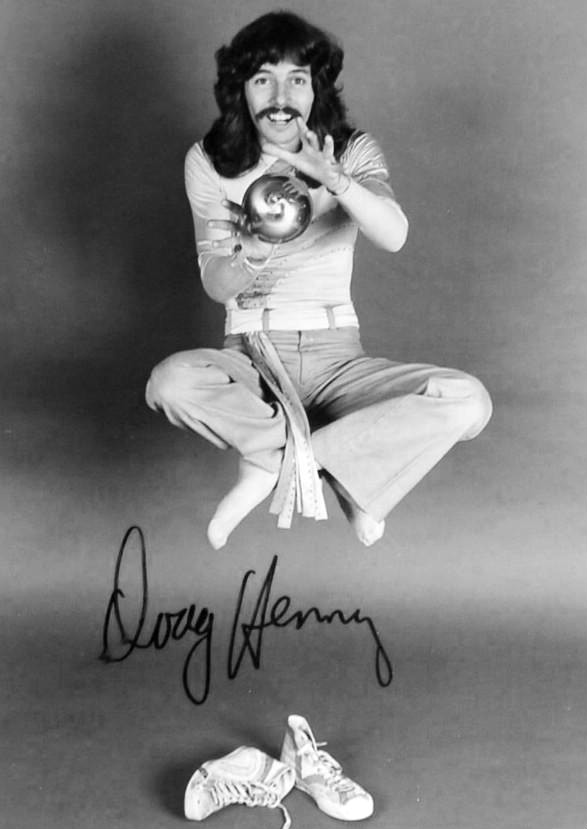

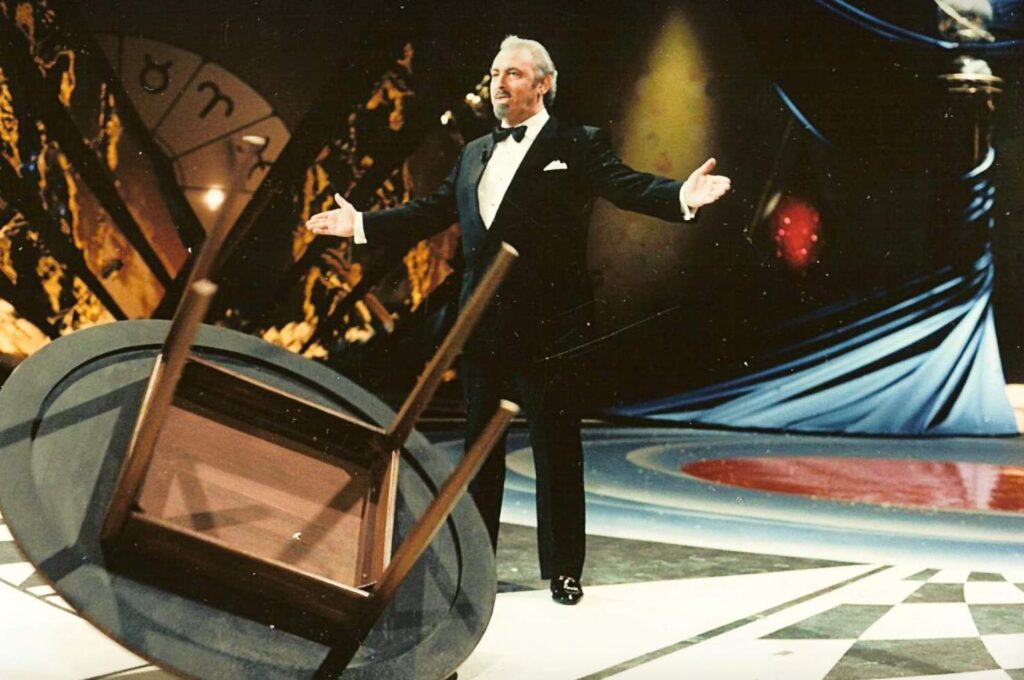

David Copperfield (1956–present)

No discussion of modern magic can be complete without recognizing the titanic influence of David Copperfield. One of the most commercially successful artists of any genre in history, Copperfield’s illusions are epics woven from the thread of dreams. He enraptured audiences with heart-stopping spectacles such as making a Learjet disappear, levitating over the Grand Canyon, and the aforementioned vanishing of the Statue of Liberty.

Magic, in Copperfield’s hands, was not just a trick or an act; it was a storytelling medium. His illusions are often layered with emotional narratives, sometimes romantically charged, other times infused with the thrill of adventure. The power of Copperfield’s magic lies not in the question of “How?” but in the capacity to move and inspire, to transport viewers to a place where emotion and wonder intertwine seamlessly. His legacy is one of relentless innovation and a reminder that magic is an ever-evolving art form, limited only by the boundaries of our imagination.

David Berglas (1926–present)

The psychology of magic owes a great debt to David Berglas, the man who brought mentalism to the forefront. His “Berglas Effect,” also known as “Any Card at Any Number” (ACAAN), is a cornerstone of mentalism, an effect where the impossible happens entirely in the hands of the participants. With a career spanning several decades, Berglas cultivated an aura of genuine mystery, fostering the narrative that perhaps magic truly does exist.

Berglas understood the power of the human mind and its role in the magic experience. His performances, often involving complex mental calculations and psychological subtleties, are demonstrations of the intricate dance between the mind of the magician and that of the audience. It is this deep respect for the mental aspect of magic that has made his work so enduring and influential.

Paul Daniels (1938–2016)

Across the Atlantic, Paul Daniels captured the hearts of the British public with “The Paul Daniels Magic Show,” a staple of Saturday evening television. For over 15 years, Daniels showcased an eclectic mix of magic—grand illusion, comedy, and close-up—threaded together with his signature charm and wit. His impact was such that he made magic not just entertaining but accessible, pulling back the curtain just enough to let audiences feel like they were part of the magic.

The longevity of Daniels’ show is a testament to his mastery of the medium of television and his understanding of his audience. His magic was never pompous or alienating; it was, instead, an invitation—an extended hand into a world of constant surprise and delight.

Penn & Teller

Enter the unconventional duo Penn & Teller, who have flipped the script on traditional magic. Their irreverent approach deconstructs the art, often revealing the mechanics behind the magic, while somehow preserving a sense of wonder. They are the iconoclasts of illusion, challenging audiences to question the nature of deception and perception.

Their show, “Penn & Teller: Fool Us,” is both a showcase and a gauntlet thrown down to magicians worldwide to perform an act so cunning that it can stump these masters of misdirection. The show has become a beacon for up-and-coming talent, highlighting the diverse and innovative work being done in magic today. Penn & Teller represent the critical, questioning spirit of modern times, while their roots remain firmly planted in the fertile soil of magic’s rich history.

These luminaries have collectively reshaped the art of magic, carrying it forward into new realms of possibility. They have shown that magic—like any art—is not static, but a living, breathing entity that grows with each new performer who dares to say, “Watch closely.” Their legacies are the stepping stones upon which the next generation of magicians stand as we continue to push the boundaries of what magic can be.

In the next chapter, we will see how the torch is being passed to new hands, and modern magicians—including myself—are contributing to magic’s everlasting thread.

Continuing the Thread – Modern Magic – Kevin Blake

Hi there, my name is Kevin Blake, and I’m a magician, and chronicler of this short and incomplete history. My performances aspire to blend the tried and true sorcery of yesteryear while, like my forefathers, creating magic that holds up a mirror to contemporary culture, creating a genre of magic that is uniquely my own.

On the TV show “Penn & Teller: Fool Us,” I created a signature rap card trick, juxtaposing lyrical flow with a card trick. The purpose was to show how remixing; infusing music and rhyme can reinvigorate a classic card trick, transforming it into something wholly original contemporary.

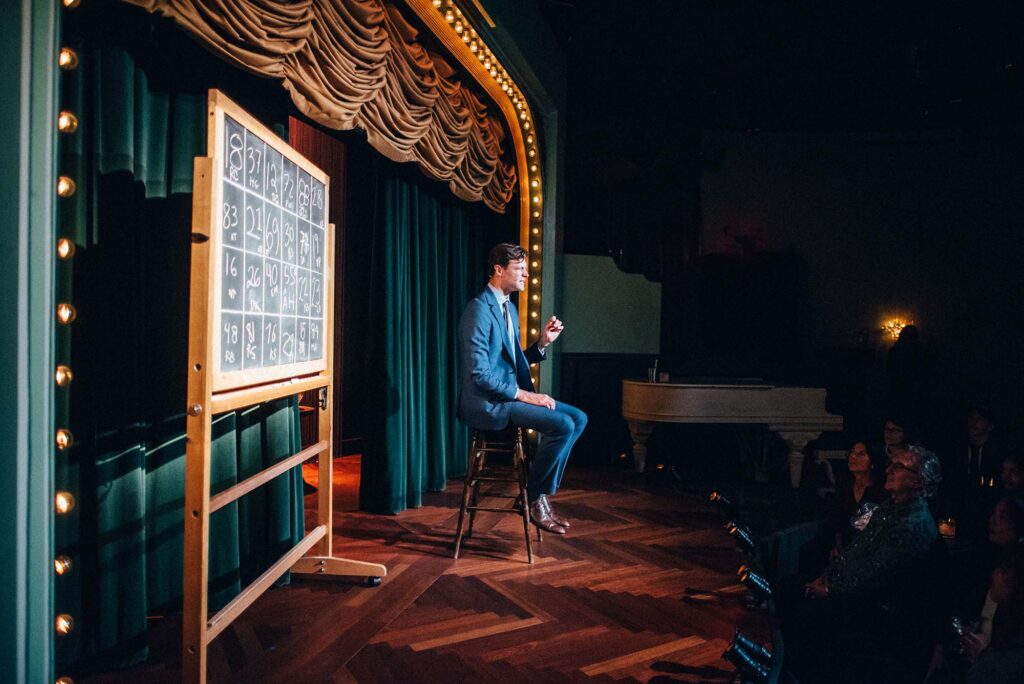

On the stage, the illusions I perform are crafted to be unique and memorable. Another signature illusion in my show is the Floating Paper Plane. A simple paper plane is thrown across the stage, only to freeze mid-flight. Another example is my distinctive approach to memorization, a feat that not only stretches the limits of mental capacity but invites audiences to consider the vast potential locked within their own minds.

In resurrecting a dice illusion beloved in the 80s, I attempt to breathe new life into the bones of the past, presenting an act that resonates with modern sensibilities while nodding respectfully to its origins. Through these acts, I engage with the audience on a level that is both intellectual and visceral.

But my contribution to modern magic is not solely about conjuring the novel from the familiar. It is about embracing the inherent skepticism of our time and allowing it to coexist with the draw of the mysterious. In showing just enough of the mechanism behind the mirage, I allow the audience a glimpse behind the curtain, not to dispel the magic but to deepen their appreciation for its craft.

Join the story yourself!

Our journey transcends the binds of time and space, where the thrill of the Golden Age magicians continues to reverberate throughout such performers as myself. Watching magic live allows the audience to engage with an ever-evolving story; to see firsthand the legacy of Houdin, Houdini, and their kin as it is honored, questioned, and reinvented. I hope you join!

For showtimes, come see me live at https://sanfranciscomagicshow.com/